Industry Consolidation: Are We Better Off?

It’s a word often whispered behind a cupped hand. Consolidation. To some, the term carries with it a sense of fear, worry and concern. It’s not so much the results of consolidation that worry people but the concern about what happens in the midst of the acquisitions that cause the consolidation. Will there be a loss of jobs? A lack of clients? Fewer suppliers to choose from? And how will these acquisitions transform the industry’s landscape this year and 10 years from now?

Since 2012, there have been hundreds of acquisitions in the promotional products industry involving dozens of companies. The bulk of the larger-company activity appears to be on the supplier side of the industry, but the distributor side has had its share as well. About a month before this issue went to press, the behemoth supplier Samsonite announced its acquisition of the luxury luggage brand Tumi in a deal worth $1.8 billion. Samsonite is reportedly the largest travel luggage company in the world and Tumi, founded in 1975, is a leading global brand with net sales last year of $548 million. Four days later, Florida-based distributor Superior Uniform Group, Inc. announced it would acquire all assets of California-based distributor BAMKO, Inc. in a cash and stock deal worth $15.8 million. In 2015, BAMKO’s revenues were a reported $31.5 million.

The big may be getting bigger but small companies are still the industry’s bread and butter with 96 percent of PPAI distributor members and 76 percent of supplier members generating annual sales of less than $1 million. Let’s take a closer look at what may causing this activity and what it may mean to the marketplace.

Why The Rise In Acquisitions?

BusinessDictionary.com defines a consolidated industry as “a commercial structure where a relatively low number of companies control a rather large market share of the overall output or sales for a particular product or product type.”

New industries start out fragmented and they consolidate as they mature. A Harvard Business Review study concluded that once an industry forms or is deregulated, it takes about 25 years on average to move through four stages of consolidation: 1) Opening (which usually begins with a monopoly); 2) Scale (buying up competitors and forming empires); 3) Focus (expanding the core business and aggressively trying to outgrow the competition); and 4) Balance and alliance (at this stage the top few companies may control 70 to 90 percent of the market).

The study suggests that every industry will go through these four stages—or disappear. The promotional products industry has been around for more than 100 years.

Marc Simon, CEO of Sterling, Illinois-based distributor HALO Branded Solutions, refers to an industry’s lifecycle based on a study conducted by Emory University in the late ’90s that reviewed countless industries from automobiles to soap to beer and from heavy industries to service businesses. The study found that once an industry matured, there was one dominant player with as much as 40-50 percent market share, a second place participant with 20-25 percent share and a third major participant with 10 percent or more. The balance was then comprised of a number of small, niche players—each nimble and with appeal to a subset of the industry, and comprising less than five percent of the market. The study argued that those companies with between five and 10 percent market share are in “the ditch”—they are too small to compete with the large players and not nimble or specialized enough to compete with the small players. The report showed these companies are most at risk of perishing.

In a PPB article last summer which addressed the industry’s relatively flat 2014 sales, Gemline CEO Jonathan Isaacson said, “For a long time now it has been obvious that the industry is mature. As an industry matures, it doesn’t mean that individual companies cannot grow, because they can.”

One way companies can grow is through acquisitions, but the reasons for acquisitions are far more specific. In two words, market share. The increase in industry acquisitions in recent years is the result of a combination of investments needed (production, IT and compliance), and margin pressure, says Emmanuel Bruno, vice president/general manager North America, for Tampa-based BIC Graphic. “Currently no distributor has a market share above five percent and only one supplier is above five percent. Both are looking for ways to grow share, and acquisitions can be a way to do it.”

Another reason for increased industry activity, especially on the supplier side, is cost and increased efficiencies through acquisitions. “When Company A and Company B can tie their back-end operations together, they can trim costs and drive value to their organizations,” says Mark Graham, president of Toronto-based promotional products software company, commonsku, and distributor RIGHTSLEEVE.

Another factor to consider, says Graham, is the rise of motivated outside investors with private equity funds who put together financial transactions that will increase the efficiency of one or both companies. “Professional investors are looking for returns and they are seeking out opportunities within our industry.” The third reason he describes is sameness, commoditization and lack of differentiation in the industry. “It can be difficult to compete if you are a me-too supplier and especially if you are a smaller supplier because you can’t get the scale to run your business efficiently and leanly.” He believes one way smaller suppliers can continue to grow and compete is if they are part of a larger entity. The solution? Acquire or be acquired.

It’s a scenario David Woods, MAS, president and CEO of Neenah, Wisconsin-based distributor AIA Corporation, agrees with, adding that it’s happening for both suppliers and distributors. “As the cost of doing business constantly rises, major investments in technology and new services are required to be competitive,” he says. “Efficiencies come with scale so there is a natural trend to find growth through acquisitions.”

Chuck Fandos, CAS, U.S. CEO of Brand Addition in St. Louis, believes supplier consolidation is driven largely by a fear of not being competitive, especially with technology and product safety regulations, and also by the needs of private equity owners. “When larger suppliers are owned by private equity, the owners are looking to grow the business in the early to mid years and sell it in three to seven years—and that drives consolidation too.”

While consolidation on the supplier side is often driven by the attractiveness of efficiencies with better tools and better pricing, there’s still another explanation. Gary Haley is president of Beacon Promotions, a supplier that has acquired 11 companies and added numerous product lines since 2002. He says suppliers are acquiring other companies chiefly to round out their product lines. “You can develop a product line from scratch [such as the calendar line Beacon built] but sometimes it’s better to buy because you get traction in the marketplace and a brand name,” he says. “When we bought product lines, we bought expertise.”

On the distributor side, it is also important to consider demographics. In the next 10 years, the age of distributor owners will be a huge driver toward aggregating within networks, says Fandos, whose distributorship was acquired by the global promotional merchandise company Brand Addition in January. “You have this huge bubble of owners over 50 who are thinking, ‘What are my options? What is my exit strategy?’”

Michael McKeldon Woody, CAS, president and founder of consulting firm International Marketing Advantages, Inc., in Cranston, Rhode Island, and a former supplier company executive, attributes the current acquisition activity primarily to the numerous small suppliers who don’t have sufficient buying power in China, nor the assets they need to deal with product safety and compliance—and the stress it puts on their bottom line. Plus, he says, margins in general are shrinking in this industry and suppliers must be operationally excellent to efficiently process thousands of small, customized orders. “Larger suppliers, because they receive a critical mass of orders, can afford to invest in the systems and processes needed to deal with that order flow,” he explains. “This is a challenge for many smaller suppliers, so some are more open to selling at this point.”

Taking A Closer Look

The aggregation of companies potentially leading to consolidation is not unique to the promotional products industry—it is prevalent across a number of industries from technology to manufacturing to pharmaceuticals. In the tech space, in particular, Microsoft, Google and Facebook have been on an acquisition spree in recent years. When Facebook acquired WhatsApp (a text messaging service) in 2014, it did so in order to acquire a new service that it did not currently possess. Graham explains that many of the acquisitions he’s observed in the promotional products industry have a different goal than Facebook’s strategy. For example, he says when apparel supplier alphabroder acquired Bodek and Rhodes in December 2015, he saw it as a way for the company to increase scale, drive down costs and be in a position to better negotiate with its suppliers. Graham calls it a very smart business strategy but different from acquiring a company to expand into a different line of business (as Facebook did to expand beyond social networking into messaging).

Jeff Schmitt, MAS, account executive at mid-sized distributor Cedric Spring & Associates in St. Charles, Illinois, predicts that distributor acquisitions are going to heat up even more over the next few years. The reason? To better service their clients. He cites that many small distributors don’t have sufficient resources, especially for things like servicing global clients. But by pooling resources and capital, they can take advantage of the assets and experience of larger distributors. “Our clients are getting more and more global,” says Schmitt, whose company recently purchased the assets of two small distributorships and recently began servicing the Germany-based parent company of a longtime U.S.-based client. “The reason I was able to pick up those businesses is because of our resources.”

Beacon’s Haley says what is happening to the promotional products industry is taking place in a lot of industries. “I think we are in a constant evolution as businesses shake out,” he observes. “We continue to be an attractive business both from a supplier and distributor side.”

What makes the industry attractive to some investors is its consistent profitability, asserts Frank Krasovec, an Austin, Texas-based investor and former principal at Norwood Promotional Products. “It’s an industry that lets you make money, but on the supplier side you have to be very efficient to make a profit,” he says, citing the amount of work required on a typical $200-$600 order. He thinks that one of the downsides that can occur with investments from private equity firms is that they have a tendency to generalize when they consider investing in a promotional products supplier and think they can save money by merging overhead costs. He says when this happens, customer service is often glossed over as though anybody can do it, when in fact superior customer service is what makes the difference between preferred suppliers and everybody else. “If they try to consolidate plants, they may save money but they lose customers. In an industry where products are time-sensitive and personalized, customer service is everything. If you mess with customer service, you are asking for trouble.” He believes industry investors are better served by putting money into making the company’s customer service operation of the highest quality instead of trying to reduce costs. “Think big and act small,” he advises.

However, Woody challenges the notion that the industry is an attractive buy to every investor. “We don’t know how many have looked at the space and said, ‘It’s not for me,’” he says. “When private equity investors take a closer look and see the relatively low barrier of entry, the commoditization of industry products, the threat of being disintermediated, large advertisers buying directly out of China and margins that are challenged, they may conclude it’s easier to make money somewhere else.”

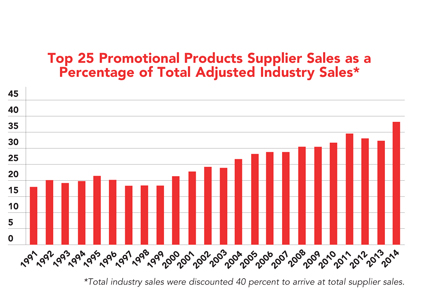

Charts provided by Michael Woody as published in IMA Media Report.

What Will Consolidation Mean To The Industry?

Woody remains a skeptic about true consolidation happening at all in the promotional products industry citing the definition of an industry that’s ripe for consolidation as one with relatively high barriers to entry, differentiated products, well-established brands and high profit margins. “None of that describes the traditional promotional products marketplace,” he says. “Margins are stressed, products are commoditized and barriers to entry are low. I’ve been tracking supplier and distributor consolidation since 1991 [see charts] and it’s clear that if we define consolidation as most industries do, there has been virtually no consolidation on the distributor side and only moderate consolidation on the supplier side.”

True to its definition, if consolidation is happening, it’s likely to create mega companies and together with the efficiencies borne by the collaboration of talent and systems, will result in companies poised to do a sufficient job of servicing their core business. However, the potential lack of competition could hinder aggressive pricing to distributors.

Nonetheless, AIA’s Woods sees the trend as positive leading to stronger companies that are more equipped to compete, and because there will be fewer companies, they are likely to be more competitive and able to innovate. “Companies that can remain flexible and able to adapt to end buyer needs will continue to do well—especially distributors with creative approaches and strong use of technology and supplier companies with innovative, new products,” he says.

Brand Addition’s Fandos thinks consolidation will actually help the industry from a product safety point of view. “It will mean a smaller number of suppliers will have the ability to drive more margin because of fewer competitors, and they will be looking to cut their costs.” Whether good or bad, another result, he adds, is that those companies will likely lose their traditional family feel and become more corporate in structure and culture. As a result, “They will also be more financially driven, not emotionally driven,” he adds. “It’s probably good for large end user clients but I’m not sure if it’s good for our industry. But we are a mature industry and we’ve got to find efficiencies. Size is often the best way to do that.”

While most industry experts predict that continued aggregation of supplier companies, in particular, will lead to the big getting bigger, some believe there will also be a very important place for small companies in the industry’s future. Graham, for one, is optimistic about that future industry landscape because of the opportunities it affords not only to small suppliers but to distributors. “We’re going to see an emergence of longer-tail-type suppliers—smaller, innovative companies who come to the market and get attention with innovative products that bigger suppliers are not interested in because they don’t match their business model, are too risky or don’t meet the requirements of their inventory or spend. So they ignore them. That’s where the market almost corrects itself,” he says.

He also believes these Goliaths may have increased efficiencies but they run the risk of creating boring products because those products are safe to buy, easy to inventory and there’s a market for them. Out of that environment a space is created for smaller to mid-sized suppliers to come in with unique products to round out the product selection in specific categories. “I’m very optimistic about where the industry could go,” he says. “I see an industry of huge players but I also see an industry of innovative players because they come to market with unique product offerings.” He predicts these innovative companies will come to market and be able to build successful, high-margin and high-growth companies that fill a product need that the big suppliers can’t. “It’s not to say they can’t fill it, but it runs against their business model in terms of scale and efficiencies—like fitting a square peg in a round hole.”

For many distributors, the potential lack of product differentiation and product innovation is the biggest fear in talking about consolidation. “Without it, we’d be competing [solely] on price,” says Graham. “A supplier may not care about that but from a distributor perspective, why do I want to sell the same mug that 25,000 of my closest competitors are selling? It’s a race to the bottom. If that’s all I’m relying on, my business is going to hit a ceiling pretty quickly.”

He emphasizes the need now and in the future for both small, unique companies and also large, turnkey operations. “Innovation is what cuts through the noise,” he adds.

BIC’s Bruno predicts fewer players but larger players if the current scenario continues to play out. “Consolidation will continue until we get companies with significant market shares,” he says. “The larger they will be, the more market share they will gain moving forward.” He also believes consolidation will reinforce relationships between large distributors and large suppliers, and that these companies will continue to become more powerful industry players.

Technology is also seen as a key component in a competitive strategy, especially among small industry players. “We, as an industry, have to look at the fundamental relationship between distributors and end users, and distributors and suppliers, and look for technology to offer better service, better products and better solutions,” says Fandos. “I’m bullish on the industry going forward, if we can do that.” He adds that those companies that don’t add value or add diminishing value to the market are likely to get squeezed out.

The Industry’s Potential Five-To-10-Year Silhouette

Fast-forwarding to the near future, Krasovec is another who thinks the industry will improve efficiency most through the use of technology—especially data-driven marketing where companies collect and analyze the buying habits of customers and market to them based on prior purchases, and individual needs and interests. “The end product isn’t much different but the process to get it there is totally different compared to five years ago, certainly 20 years ago, and it’s all related to technology.”

Given the industry’s recent history, Graham thinks the time is ripe to see some blockbuster acquisitions over the next two years as the big companies get bigger by combining resources. He believes this leaves mid-sized companies in a precarious position—not big enough to maximize efficiencies and scale but not small enough to be nimble and innovative. He characterizes this position as “caught in the middle.”

“In the next two, five, 10 years we are going to see the hollowing out of the middle—it’s a scary place to be,” says Graham, whose distributorship can best be described as a small-but-thriving company. “We strive every day to create a business that is not in the middle but in its own league. You could be an average me-too $10-million player or be a very differentiated $10- million player.”

Will The Industry Be Better Off?

“Thoughtful, controlled consolidation will make us better off but if consolidation means that in five years we’ll have 10 distributors and 10 suppliers, I don’t think that’s good,” says Fandos. “We need enough companies who bring energy, fresh ideas and young people into the market. You want a pipeline. What the market is telling us with consolidation is it’s not as efficient as it can be. If we can get more efficient, and efficiency means safer and better, then that’s a great thing for our industry.”

The scenario then begs the question, is there an optimum number of supplier and distributor companies? That’s an unknown entity, but most agree that the market itself is the best determiner and will dictate the eventual outcome.

HALO’s Simon thinks the industry will continue to adapt to meet the needs of the marketplace. “As a result, the industry will become stronger, and our powerful and compelling value proposition will become clearer to our potential customers,” he says. Will the industry be better off? “Any trend that makes our industry more competitive is good for our industry,” he adds.

Bruno also believes the industry needs to adapt to the changing market. “The industry as we know it is much too fragmented to be able to invest in new technologies or in compliance in order to face new competitors in the future. Whether it is better or not, I don’t know, but it’s a necessity,” he says.

The future that Graham sees offers plenty of opportunity for the industry to be better off. He predicts the continuation of acquisitions as producing an interesting mix of big suppliers who fill their role efficiently matched with a growing number of small, niche suppliers. “It introduces an environment where other players can grow up,” he explains, likening the potential scenario to a fallen log on the forest floor. “When a tree dies, it becomes a nurse log where other trees grow out of it. The exact same thing can be applied to the industry. As companies merge or acquire, it opens up an opportunity for a more nimble competitor to take market share from the larger player and you’ll have players that will move into the areas left vacant by the companies that have been acquired.”

Other distributors see the result of aggregation and consolidation among suppliers as potentially limiting their resources for products—a trend some are already experiencing.

Debbie Abergel, senior vice president, marketing/sourcing at Los Angeles-based distributor Jack Nadel International, has noticed that when she’s in a client-bid situation, other distributors vying for that piece of business are sourcing from the same suppliers. “Suppliers are not as aggressive on pricing as in the past,” she says. “One basically told me that he was going to get the order one way or another anyway. We used to have five or 10 suppliers that had the same item and we could get a better price, but we don’t have that advantage anymore.” She is also concerned about the increase of me-too products and the loss of innovation as suppliers aggregate. “We like telling our clients we have 5,000 suppliers in our database. Suppliers want all of our business but we don’t want to tie in all of our business with a handful of suppliers. We like to have choices.”

And while she doesn’t see a lot of product innovation currently in the industry, she is seeing it in the services arena in areas such as decorating, new processes, smaller runs and quicker turns. Still, the potential for limited product resources is cause for concern but she believes distributors will be resourceful and willing to dig a little deeper to find fresh ideas to serve their clients’ needs. Abergel also likes the idea of suppliers that can create private label lines and believes it’s important for suppliers to give thought to the positioning of their product brands when one company acquires another. An example is the retail brands Banana Republic, Gap and Old Navy. All are owned by the same parent company but through careful positioning, each brand is distinctive and stands on its own. “It will be up to suppliers to show the lines they bring on as boutique lines, and to continue product development for those lines as well,” she adds. “It’s all in the execution.”

While there are upsides and downsides for suppliers and distributors, savvy salespeople are most likely to be the ones to find the bright spots in the scenario. Those who are let go because an acquisition created a redundant sales force are expected to be snapped up by another company interested in harnessing and leveraging their talent, skills and experience.

“After the dust settles, there are definitely opportunities for people on both sides of the fence,” says Craig Reese, senior vice president/director at Jack Nadel International. “From our perspective at JNI, people don’t like change and when two distributors join forces, it’s a chance to entice good people to look around and make sure they’re working for the best company. The same holds true for suppliers. It’s an opportunity to find great regional managers and to take advantage of the inevitable issues that confound two companies joining forces.”

Where Do We Go From Here?

While Woody remains a skeptic about a fully consolidated industry, he’s careful to make a distinction about the industry’s future. “For years we believed that the health of the traditional distributor network and the health of promotional products as an advertising medium are one and the same. They are not. I’m very optimistic about promotional products as an ad medium. But will $20 billion worth of business continue to go through the traditional channel? Some will, but there will be some leakage too.” He predicts fewer suppliers in 10 years because of the commoditization of the products but strongly believes there will always be room for large suppliers that import, decorate and turn orders in 24 hours. “Those orders will always go through the traditional channel. Large suppliers that are warehousing products, pulling them off a shelf and shipping in two days will do fine because there’s no other place for those orders to go.”

Graham is expecting a slightly different scenario based on market demand. “I don’t see an industry of five big players that sell highly optimized, efficiently produced and sourced products. I just don’t see it. I think how bad it would be if, in 10 years, the industry was ‘owned’ by 10 companies. That would be a bad environment. But I don’t see it happening because we have a medium that is much in demand. End clients are hoping for innovation and creativity—they don’t always get it but that’s the fundamental hope in what we are selling. What’s new? What’s innovative? What will blow my customers’ minds away? If that’s the assumption, then the market will always meet that demand.”

This article is intended to provide perspective in relation to consolidation issues in the promotional products industry. PPAI does not endorse any particular pricing model or market approach. PPAI is committed to ensuring that competition within the industry is uninhibited by any express or implied regulation of prices or quantities of goods or services in the market or through any PPAI publication provided for the benefit of the promotional products industry as a whole.

Tina Berres Filipski is editor of PPB.